Backdoor Vulnerability in Gateway Used by Spammers

March 3, 2017

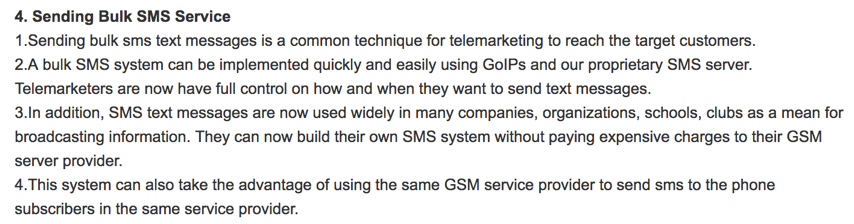

I’m not sure whether to laugh or cry about this one. Trustwave’s SpiderLabs just blogged about an unpublished backdoor they found in a device used to send SMS spam. It’s called a GSM VoIP Gateway (GoIP) and it looks like this:

The device is straightforward. Put up to 32 SIM cards into those slots on the left, and for each of those SIMs, connect an antenna in on the right. Plug the thing into your network, and you’re in business. Think of it as 32 cell phones all being centrally controlled. DBL Technology makes an array of them. From their web site:

GoIPs have other uses too- we’ll get to them later…but these things make spam “bulk SMS messaging” a snap. Get a number blocked for sending too many messages? Just swap out the burned SIM and you’re back online. Lock yourself out? It has a handy backdoor to get you back in…just telnet (yay!) and say the magic word. Well, at least the magic username.

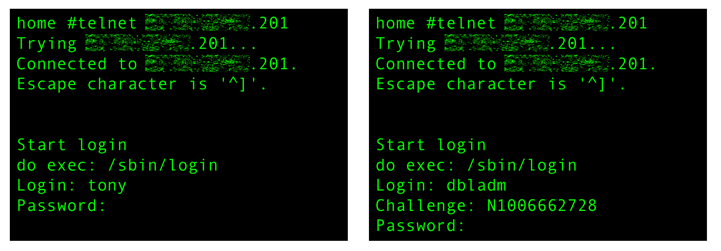

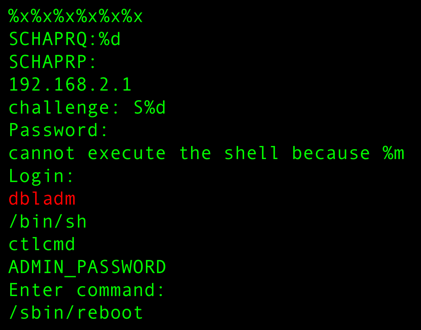

Spot the difference:

The dbladm user is special. It isn’t asked for a password like I am; it’s presented with a CHAP-like challenge message.

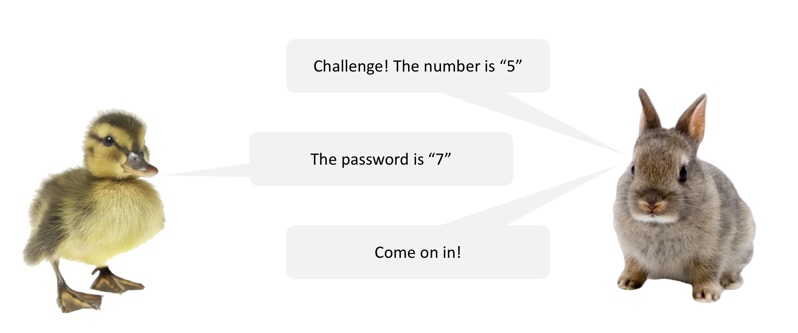

In a nutshell: instead of needing to remember a password, dbladm needs to know a secret function: a bit of math that can be done against the challenge message. It’s ducks-and-bunnies simple…really. Imagine Mr. Duck and Mr. Bunny work out a system in which the password equals the challenge number, plus two. It’d look like this:

Easy. Trouble is, I checked the documentation for the GoIP: it doesn’t mention dbladm anywhere. So DBL has implemented a way to log into their devices that they aren’t telling customers about. That’s slimy. I wish this was a stand-out example, but D-Link was caught doing this a few years ago, and we routinely see this stuff when we do assessments.

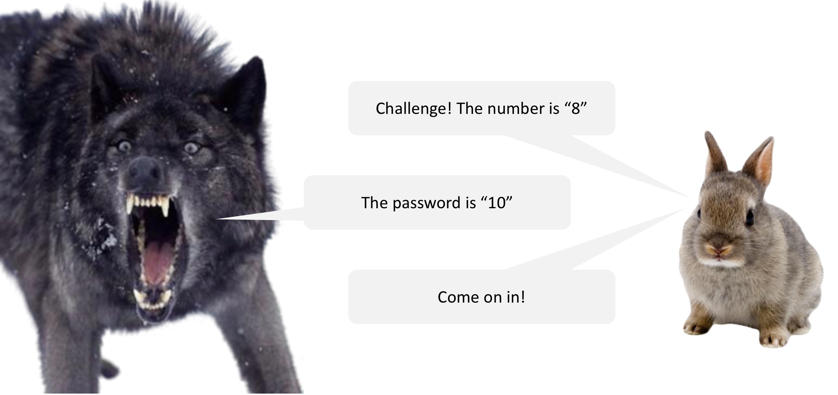

I don’t like it, but setting morality aside for a moment: If you’re going to do something, slimy or not, at least do it well. Don’t make a backdoor so loose anybody can just walk through it. Let’s go back to Mr. Bunny:

His challenge number can be anything, and it can/should change each time, but it’s pretty important to keep that “plus two” business a secret. Anyone who knows the function can get in, and things could get bad if undesirables were to learn about it:

DBL didn’t make their math much tougher than Mr. Bunny did, and it seems they did an even worse job protecting it. The meat of the function is below; just sub in the challenge message for r6:

‘r2 = r6 + 20139 + (r6 >> 3)’

That function (covered in detail in the SpiderLabs blog) is stored in the device’s firmware, which is publicly available. This was true security by obscurity: the only thing protecting DBL’s customers was a belief that no one would try to reverse engineer the firmware. There were no obfuscations or other countermeasures. After reading the blog it took me less than 15 minutes to download the firmware, unpack it, and find dbladm.

Hang on though- it gets more cringeworthy. DBL released a version of their firmware that fixes this issue, but:

- The backdoor was left in place (they just made the math a bit trickier)

- They don’t have automatic updates (so customers have to download and install the “fix” manually)

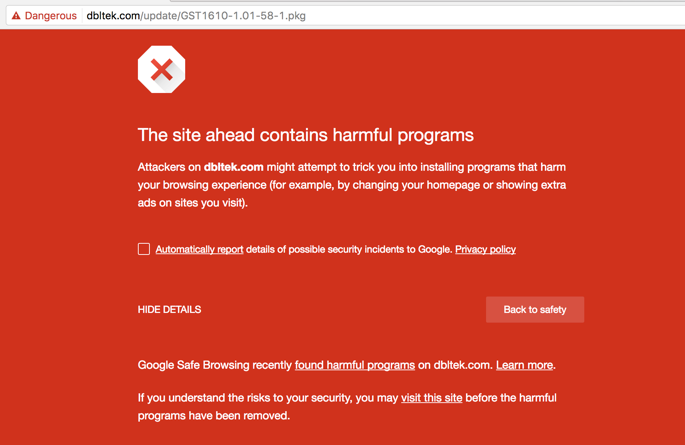

- Customers trying to download the firmware are greeted with this:

It seems like our best chance is that DBL puts their backdoor to good use and patches things for their customers. Woof.

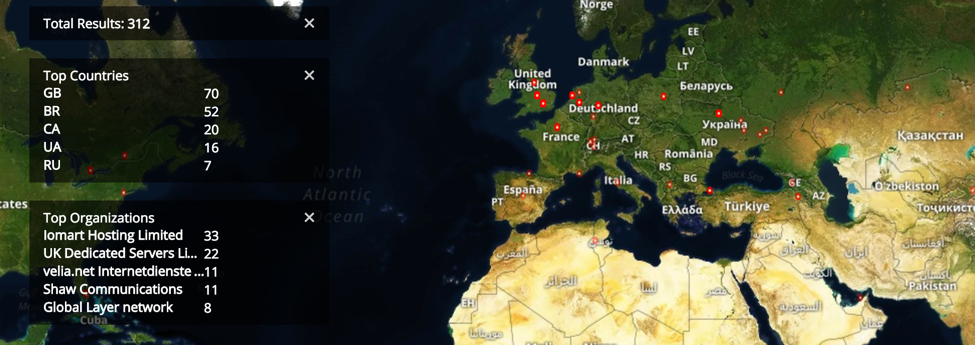

Not that it’d do much good if they did. Now that we all know where this is, how long before someone else reverses the “fixed” version? A quick search on Shodan netted about 300 of these things. People have got to be crawling all over them by now.

And yeah, DBL markets to spammers- I’m not shedding any tears for them. But there are also legit uses of these products, and that means there are probably some nice people out there who are now exposed. That sucks, because nobody wants unauthorized people intercepting/rerouting their calls.

If you want to learn how someone would reroute inbound/outbound calls, check out section 3.3.7 of the GoIP’s manual.

That’s it for now. In my next post I’ll give a quick demo of some of the methods used to find vulnerabilities like this with basic reverse engineering techniques.