Reversing Firmware- How does that work?

March 8, 2017

Last week I wrote about a backdoor vulnerability in a device used by spammers. The team at Spider Labs discovered it by reverse engineering a piece of firmware. If you’ve never seen anything like that before, here’s a quick walk-through that’ll take a piece of firmware from a binary file to an extracted file system you can explore on your own. Let’s get started!

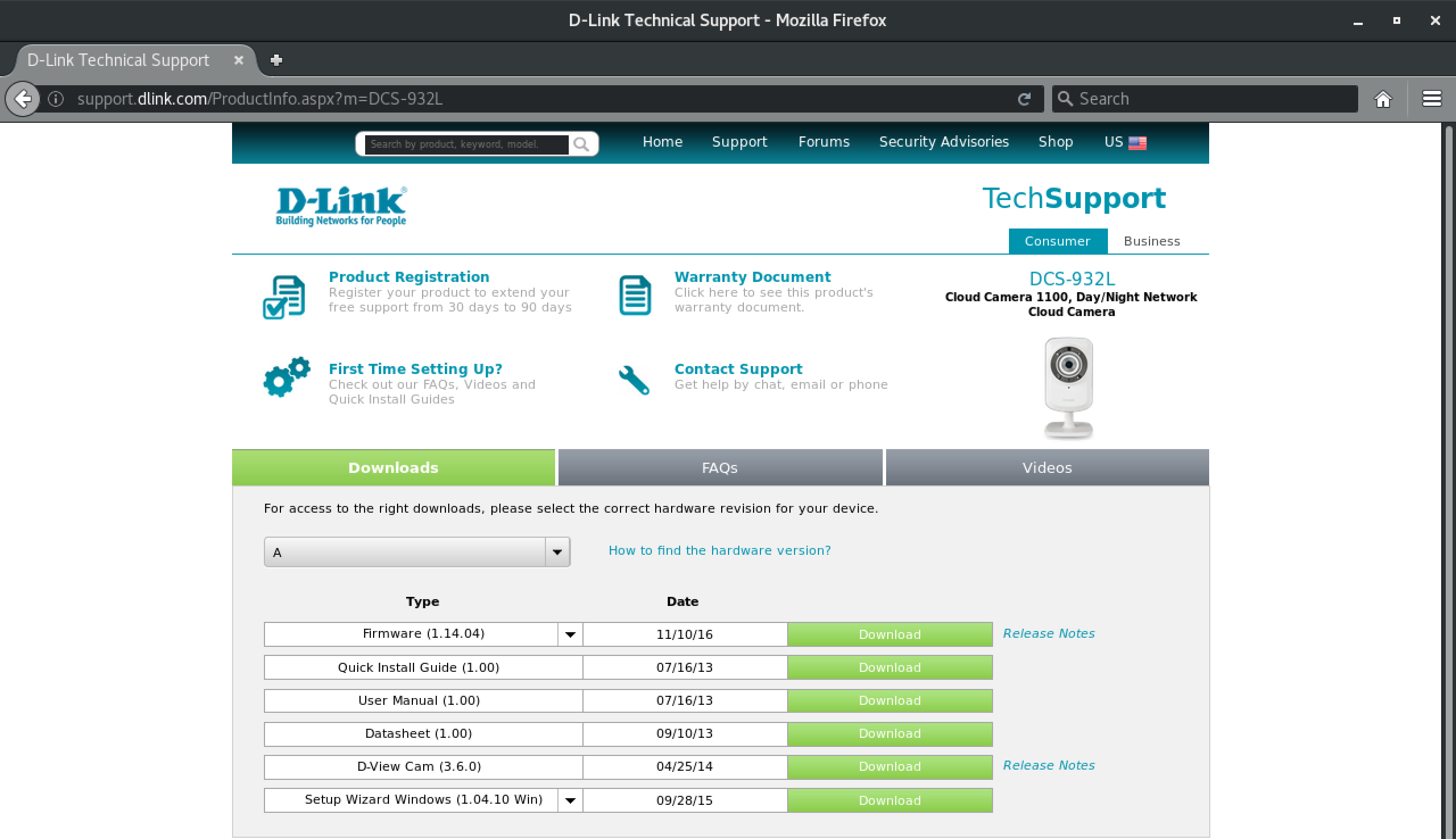

1.) Download the firmware

Download the firmware from D-Link. This walkthrough used hardware version A, firmware version 1.14.04.

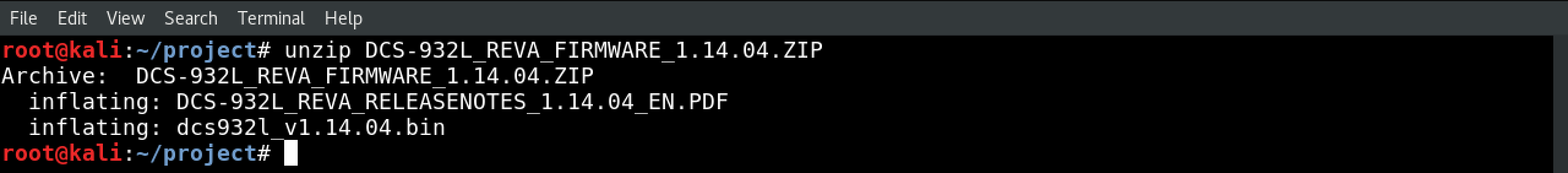

2.) Unzip the archive

Unzip the archive with unzip DCS-932L_REVA_FIRMWARE_1.14.04.ZIP. You should see two files in there: a PDF, and a .bin (binary) file.

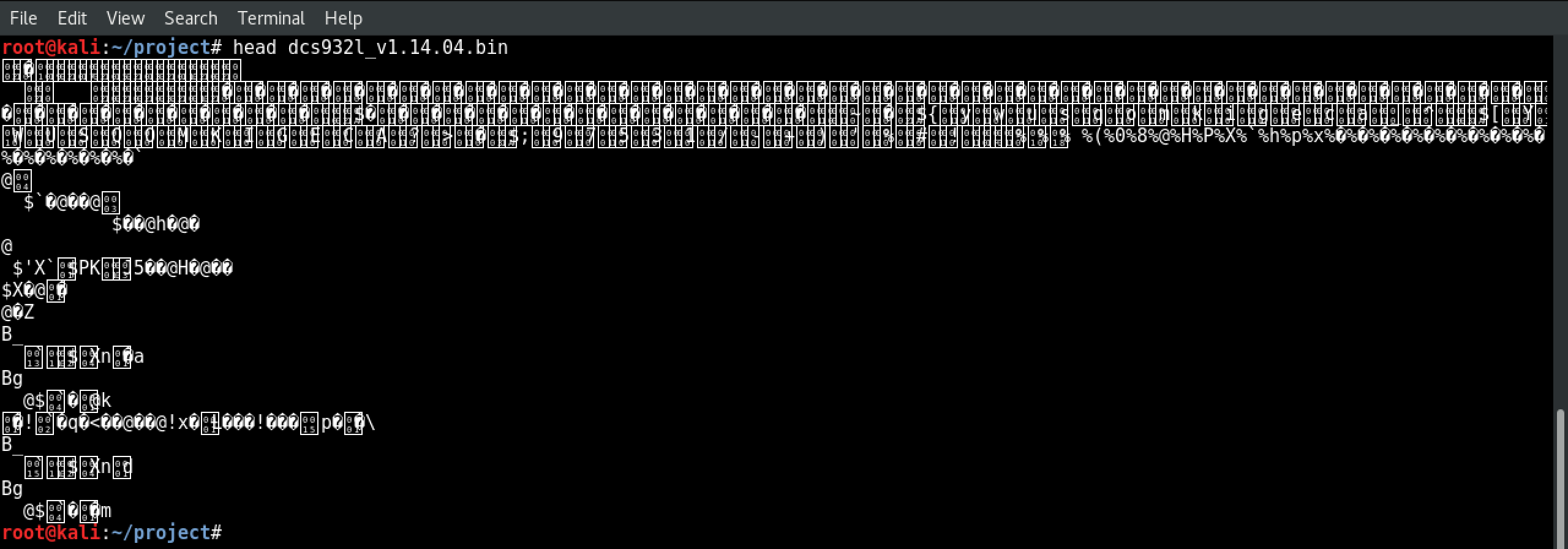

3.) Try to read the binary file

(Optional)

Binary files are formatted for computers- not human eyes. Try reading that binary like you would a text file by running head dcs932l_v1.14.04.bin.

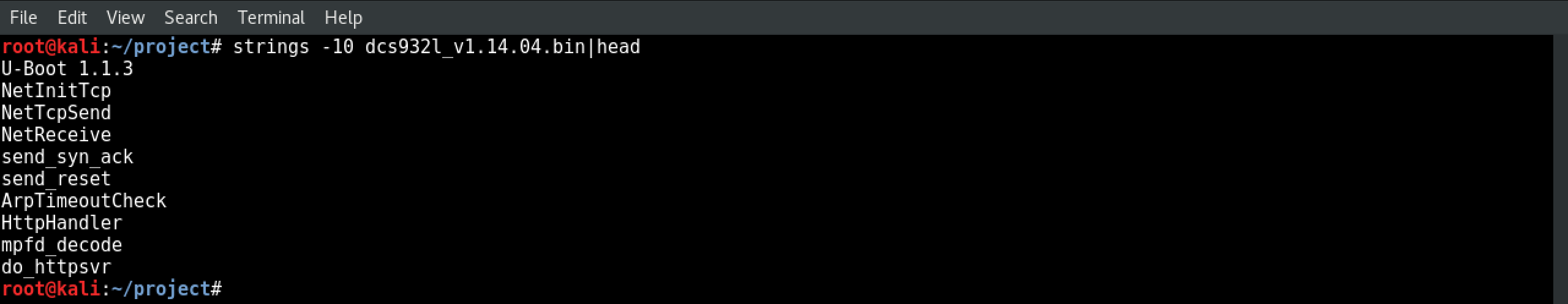

4.) Use strings to see printable characters

Try running strings -10 dcs932l_v1.14.04.bin|head to search the file for printable characters. The -10 tells strings to search for 10 or more printable characters in a row, and| head cuts the noise down by only showing you the first 10 lines things it found.

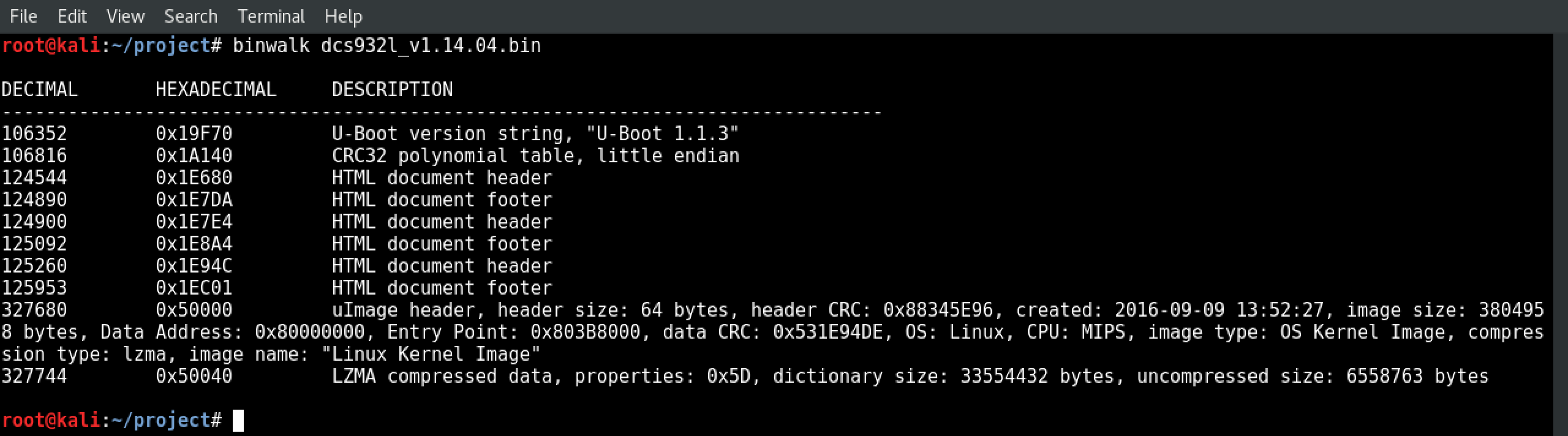

5.) Use binwalk to orient yourself

Now it’s time to use binwalk, a tool specifically designed for reverse engineering. It will parse the file and return a table of contents based on what it finds. Try running binwalk dcs932l_v1.14.04.bin. Each “hit” binwalk gets is recorded on a single line, and comes in three parts:

- A file location in decimal format

- A file location in hexadecimal format

- A description of what was found at that location

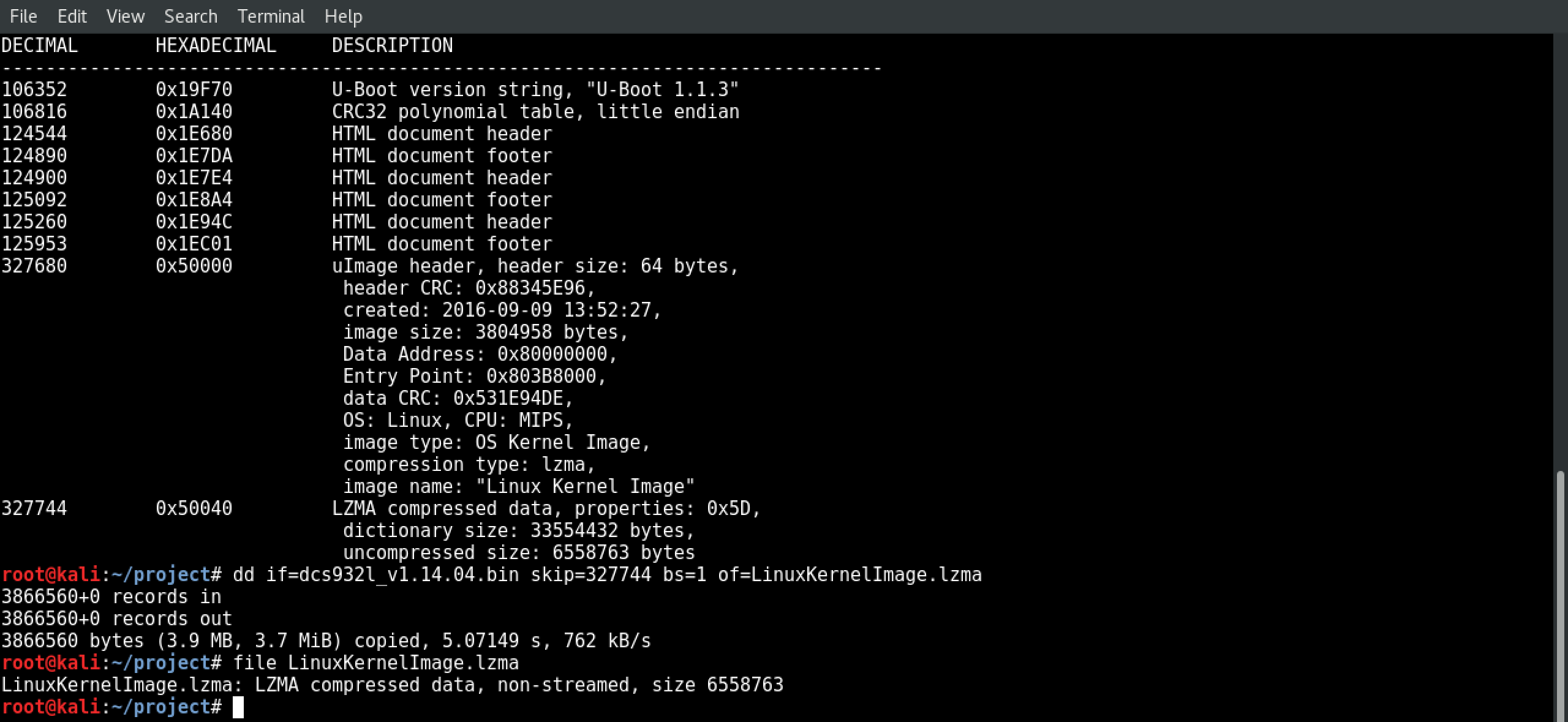

Looking at the first line, we see that binwalk found a U-Boot string at 106352. U-Boot is a popular bootloader. When a device is powered on, it’s the bootloader’s job to load up the operating system. And sure enough, at 327680, we can see a uImage header telling us that we’ll find the OS kernel image in a LZMA archive that starts at 327744. If you’re having a hard time following it, I cleaned up the formatiting in step 6.

6.) Carve out the LZMA archive

Before we can unpack that LZMA archive and dig through it, we need to carve it out of the larger binary. We’ll do that by running: dd if=dcs932l_v1.14.04.bin skip=327744 bs=1 of=kernel.lzma

(Optional) You can check to ensure the LZMA archive came through OK by running file kernel.lzma.

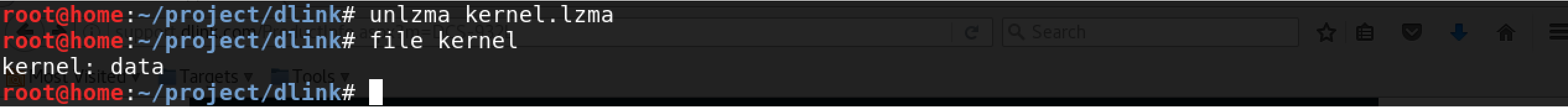

7.) Another data file…

Now you can unpack that LZMA archive by running unlzma kernel.lzma. To learn what we’ve unpacked let’s use the file command again by running file kernel…looks like we’ve got another data file.

8.) Time to rinse…

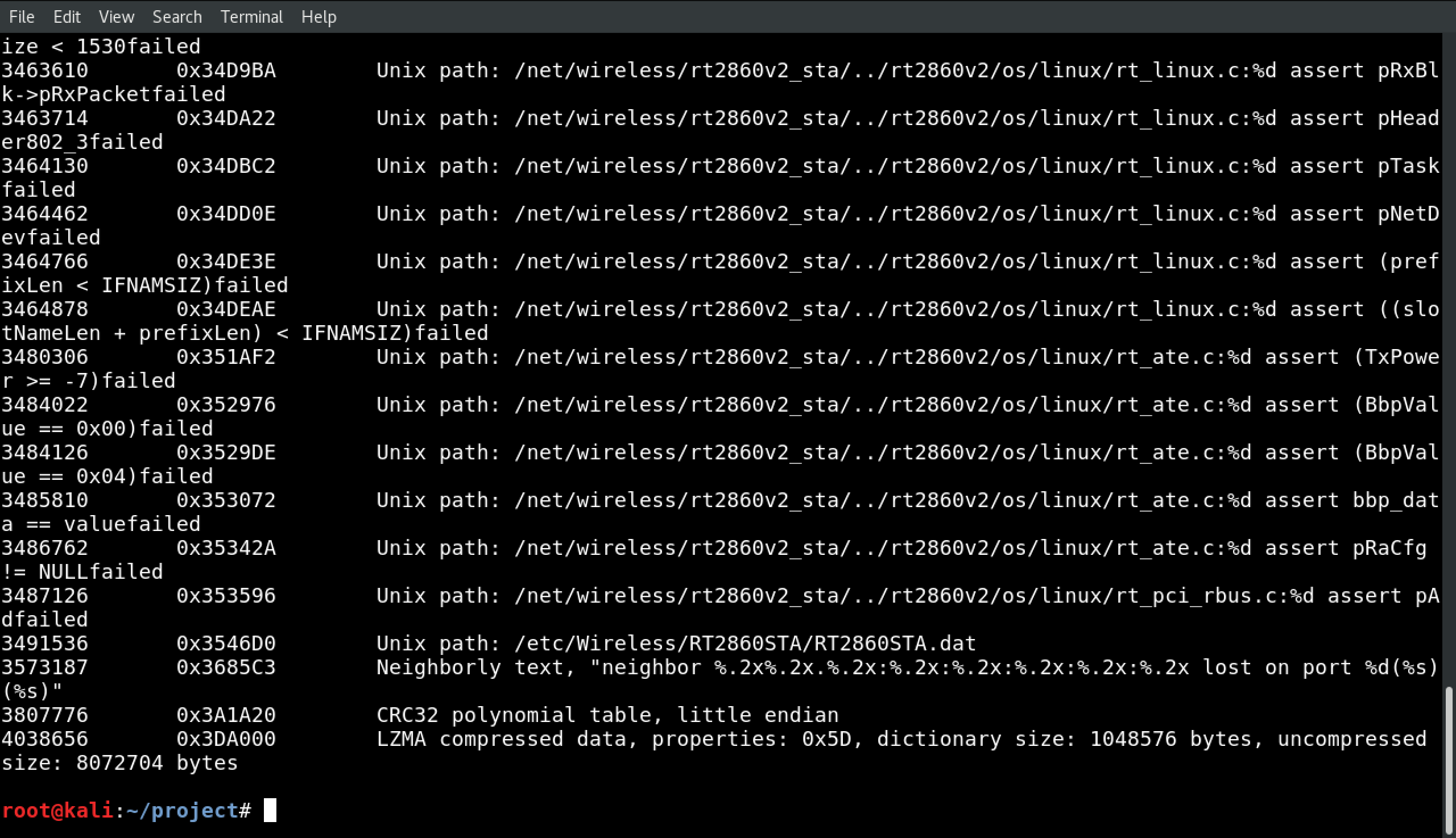

Just like before, we’re going to run binwalk against the data file with binwalk kernel.

There’s a ton of output there, including another LZMA archive at 4038656. If you scroll up to the top of the binwalk output, you’ll also see the Linux kernel version.

9.) …And repeat.

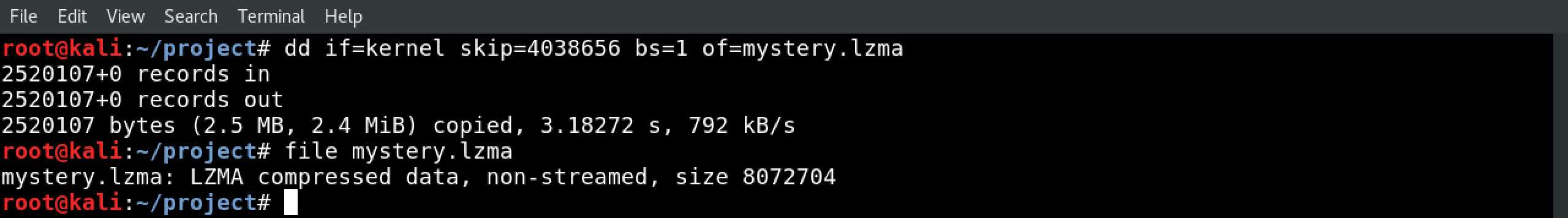

Now let’s extract that LZMA we saw in there. We’ll use dd if=kernel skip=4038656 bs=1 of=mystery.lzma, and unpack the results with unlzma mystery.lzma

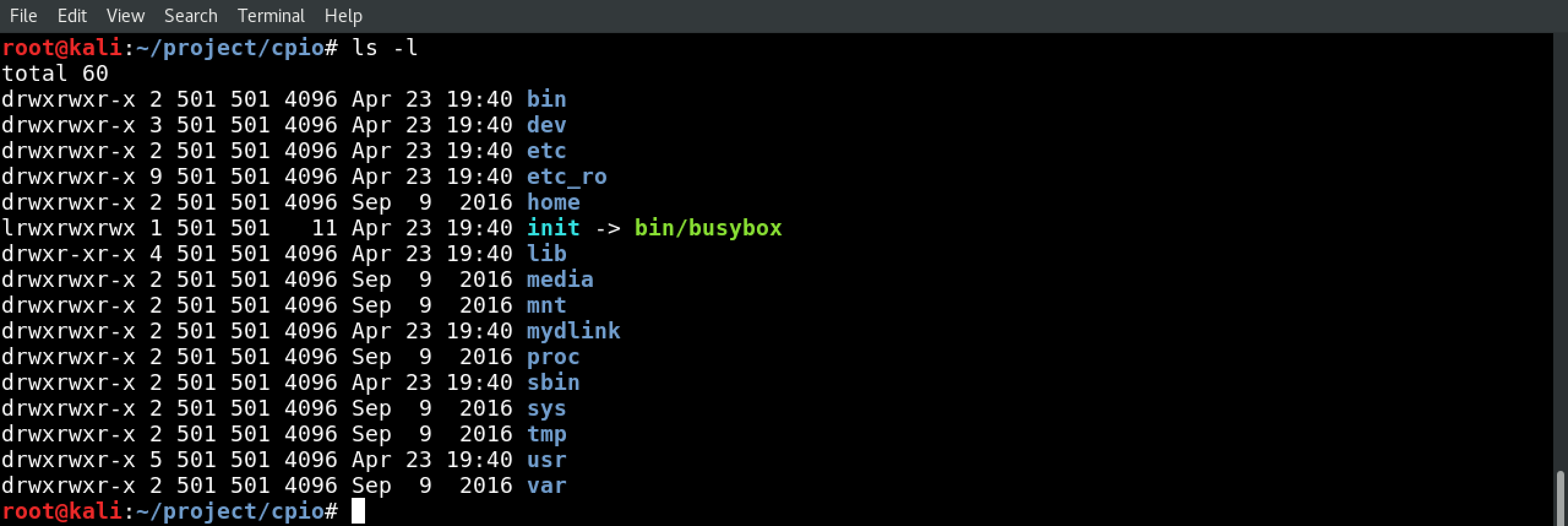

10.) The CPIO archive

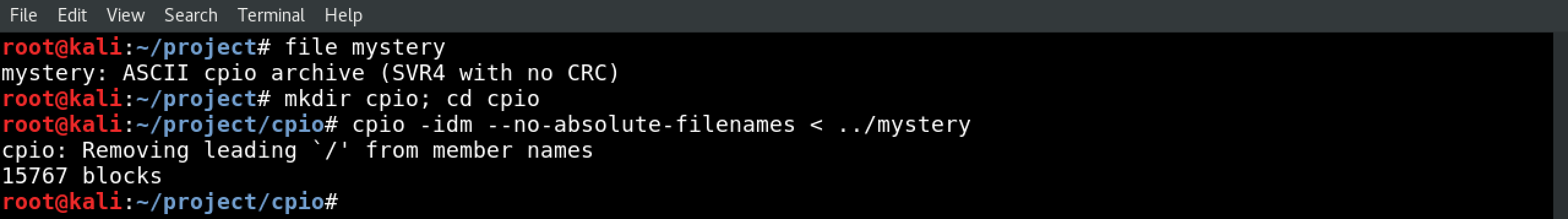

Run file mystery. It’s a CPIO archive, which is yet another archive format…and it’s the kind of place you’re likely to find the file system.

Create a directory to unpack the CPIO archive and get in there with mkdir cpio; cd cpio. Now unpack the CPIO with cpio -idm --no-absolute-filenames < ../mystery.

11.) Explore the file system

If everything went well, congrats! The file system is unpacked, and you’re able to explore it on your own.